It’s an odd thing, finishing a TV show. As someone who’s been writing for the same series for about six years now – granted, we’re not high concept drama but a long-running medical – I can’t imagine how hard it must be to write something that not only pleases yourself, but all the people involved in making the show – and in the end, the crowd. There’s so much riding on those final minutes! I mean, people still talk about the final scene of the sopranos (don’t stop! believing!) or LOST (we’ve been waiting for you). This is your last chance to reveal your hand. If you’re too obvious, people will think you’re an idiot. If you’re too open, they will think you didn’t know what story you were telling – and then think you’re an idiot.

When Breaking Bad ended, I wasn’t worried. The third to last episode, Ozymandias, was an incredible piece of television, a riveting hour in which Walter White’s entire house of cards came crashing down and almost ever promise the show made in its five previous seasons was fulfilled. For me, the show ended with that episode, and the two following episodes were an epilogue in which they would tie up Walter White’s and Jesse Pinkman’s relationship about a year after Ozymandias.

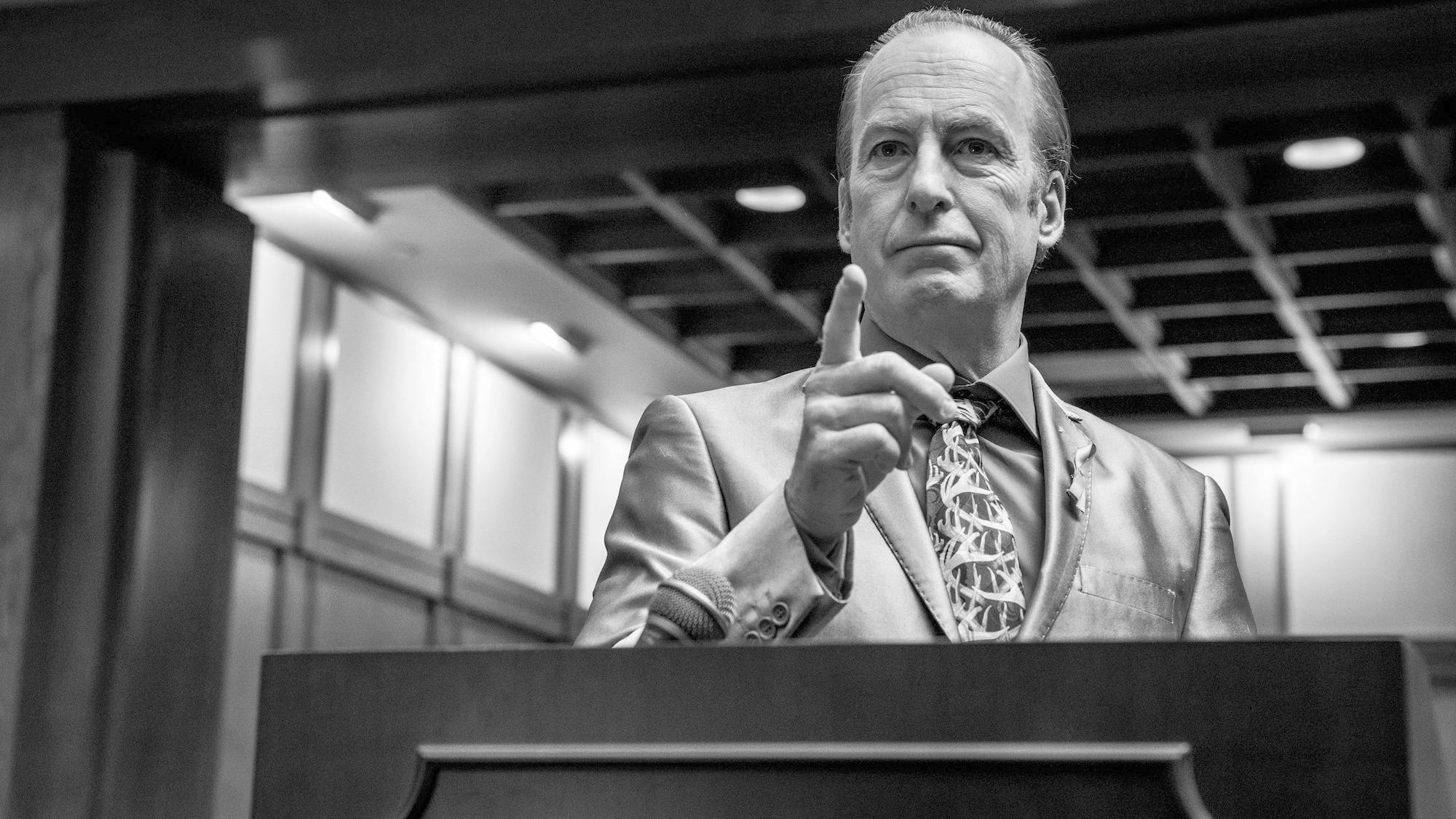

Now, with Better Call Saul, we have a similar story construct: throughout the show’s six seasons, there’s black in white scenes which function as a flashforward teasing Saul’s life after the events of Breaking Bad. The show itself, however, takes place before Walter White ever happened. For about five seasons, the black and white scenes are nothing more than fluff. Very little happens, and while watching Saul’s relationship with his brother, with Kim, with Lalo, you kind of forget about it.

As the series progressed, I grew increasingly worried. The further we went along, the more the show – which started as a courtroom drama – revolved around the doings of Gus Fring and Lalo Salamanca, two drug baron rivals who had very little to do with our main character. And when a showdown between Lalo and Saul finally happened five episodes before the series would end, I was scared of the consequences. Was this the endgame of this show? A showdown between Saul and a dude selling meth?

Turns out, I shouldn’t have worried. An episode later, the Lalo storyline ended. A new conflict – one which had been subtly brewing under the surface for six seasons – was established. And this conflict pushed the story into the future realm of black and white.

Breaking Bad’s and Better Call Saul’s cinematography is amazing. I could watch scenes from these shows all day just to admire how they were shot. They are often daring and linger on things a smidge longer than anyone would dare, and this is especially true of the final episode, which – with a few exceptions – are entirely in black and white.

It’s consistent storytelling, and it’s such a rare thing. Anyone in. the industry in their right mind would say that after one episode, the show had to switch back to its vibrant colour palette. But it never did. They had a concept and they stuck by it.

And it pays off: Better Call Saul absolutely nails the ending. The final five episodes are the best the show has made. And the finale not only finishes the series, but give an organic extra layer to Breaking Bad’s ending without retconning what arguably was and is the best show ever produced on television (fight me).

There’s so much more to say about Better Call Saul (and Breaking Bad), and I think I deserve a spanking for not writing at least three more pages about Kim Wexler, one of the most interesting characters on the show, portrayed by Rhea Seehorn. So I’ll just leave this here:

See that performance? See how they frame that? See that hand? What madman who do this? And why aren’t we all doing it?!